Description

“In 1938, the Carnegie Corporation of New York hired Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal to tell Americans about their own “race prob- lem.” His two-volume study, published in 1944 as An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, for years framed public dis- cussion of the issue in the United States.

Was it bizarre that the Americans required a professor from the Stockholm School of Economics to teach them about themselves? Not at all. Inquisitive outsiders are among those best qualified to reveal the true nature of a place.

In Canada too, many immigrants have helped define our very history. Michael Ondaatje, from Sri Lanka, immortalized the building of Toronto’s Bloor Street viaduct in his celebrated novel In the Skin of the Lion. Earlier this year, Afua Cooper, from Jamaica, published The Hanging of Angelique: Canada, Slavery and the Burning of Old Montreal, and her account of slavery in Montreal vaulted onto the Canadian best-seller list.

Joe Fiorito, a third-generation Italian Canadian who grew up in Thunder Bay (then Fort William), was born in this country, but he remains a new- comer to Toronto. A self-described “Northern Ontario boy,” he moved to Toronto briefly at the age of 19 or so, then moved away to live in Fort William, Iqaluit, Regina, Montreal and Spain.

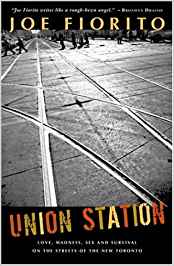

“It took me thirty years to get back [to Toronto],” he writes in his new portrait of the city, Union Station: Stories of the New Toronto.

Fiorito adopted Toronto a scant ten years ago and still sees through the eyes of a newcomer. Perhaps that is why his portraits of ordinary Torontonians are so vibrant and gripping.

There are various ways to write about a city. There is always The Big Picture—the public debates, the elections, the economy and the envi- ronment. And then there is the story of The Little People, and how, while nobody in particular watches, they get by, make their own marks in life and dance with luck—good and bad.

Canadian literary culture generally favours The Big Picture. A book about the prime minister of Canada is likely to earn more attention than, say, a story about a florist who runs a shop for 50 years in Little Italy. And yet who is to say that the story of the florist will not affect a reader just as meaningfully as the book about the politician?

If any Canadian writer can show us what makes an interesting life, and what makes an important story and how to go about defining a city, Joe Fiorito can.

Fiorito, who writes three columns a week for The Toronto Star and who is the author of a novel and three non-fiction works including the acclaimed memoir The Closer We Are to Dying, announces in his prologue that he will tell his story through people who live under the radar.

“The wrong people have all the money in Toronto, just as they do where you live,” he writes. “I am not interested in those people … There is no helping the ambitious. Let them be. They know how to help themselves. I’m interested in everyone else.”

You will not learn, in Union Station, how or why the CN Tower came to be built. But you will ride up its elevator with Joe Kiloonik, an Inuk elder from Taloyoak, a town of 900 in Nunavut.

He is a master carver and a man of few words, none of which are English. We met during his first trip to Toronto. He was brought here to demon- strate soapstone carving … We were standing at the base of the CN Tower. Joe took a narrow-eyed drag on his cigarette and looked up.

The tower—world’s tallest freestanding, etc.—is way up, all the way up. Joe said some- thing in Inuktitut to his nephew. The translation: “He said he is thinking it will sway. Just by looking at it, it’s the only natural thing it will do. He says it should at least be anchored.”

Joe Kiloonik, his nephew and Fiorito ride up the CN Tower. They look around. They get nervous. They come down.

On solid ground in the gift shop, Joe said, with the merest hint of relief,“I couldn’t even think any more up there.” Joseph [the nephew], who lives in the Western Arctic, examined a Calgary Flames cap. He was surprised by the price tag: sixteen dollars. Too expensive? Joseph said, “These cost twenty-six dollars back home.”

In Union Station you will not read about elections in Toronto (although the former mayor, Mel Lastman, earns a well-deserved poke for his disgraceful comment about fearing that he might be boiled and eaten in Africa). However, you will encounter the story of Anita, a young woman who sells her body to pay for crack cocaine, and who struggles to drop the trade and the drug.

Fiorito offers no analysis of racism in Toronto, but describes a “small brown man” who comes from Tibet and who gets nabbed for stealing a jar of skin cream from a Queen Street drugstore. Skin cream? To make himself look whiter. Fiorito does not discuss urban violence, writ large, but the day after someone shoots two riders on the Jane Street bus, he meets a 13-year-old boy who has already gone through a shooting in his own family and who says a prayer at night for the young girl on the bus who was hit by a stray bullet.

Fiorito shows us elderly people who find the bottom falling out of their lives when the super- market moves out of the apartment building they inhabit. He introduces us to homeless people who go to street corners for their sandwiches and to people without provincial health insurance who go to walk-in clinics for their stitches. He lets us know that Boris Rosolak, manager of Seaton House—a shelter that makes its own grog for its alcoholic residents—“keeps an ironic, iconic statue of Chairman Mao on his desk.” And he zooms in on a refugee who grows up in Regent Park without knowing that he lacks Canadian citizenship, and who finds it out the hard way when he falls into a life of crime and is about to be deported to Guyana—a country he does not know.

Joe Fiorito knows all too well that the great and the good in this country are not fond of the poor. In 1995, Ontario Premier Mike Harris slashed welfare rates by nearly 22 percent. In 2002, Stephen Harper’s comment about “Atlantic Canada’s culture of defeat” painted Maritimers as poor and unwilling to do anything about it. Last year, Paul Martin’s communications direc- tor warned that Canadians would blow the Conservatives’ proposed daycare handout on “beer and popcorn.”

Two things can happen when you live in one place for a long time. You can see your neighbour in a more nuanced light. Or you can shut the door and draw the blinds.

Fiorito yanks up the blinds, flings open the door and marches straight into his neighbour’s kitchen. True, he complains that nobody makes decent coffee. But at least he eats with his neigh- bours, and shows us their tastes, and leaves us with the humbling feeling that we have been walking around our own streets self-centred and stone blind. In Union Station, Joe Fiorito adds vitality and wisdom to Canadian conversations: he is opinionated but not angry, cranky but not a zealot, funny and indulgent without sentimentality.”

–Lawrence Hill, who grew up in Toronto, is a novelist and non-fiction writer.